Dear friends,

U.S. policies are driving allies away from using American AI technology. This is leading to interest in sovereign AI — a nation’s ability to access AI technology without relying on foreign powers. This weakens U.S. influence, but might lead to increased competition and support for open source.

The U.S. invented the transistor, the internet, and the transformer architecture powering modern AI. It has long been a technology powerhouse. I love America, and am working hard towards its success. But its actions over many years, taken by multiple administrations, have made other nations worry about overreliance on it.

In 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, U.S. sanctions on banks linked to Russian oligarchs resulted in ordinary consumers’ credit cards being shut off. Shortly before leaving office, Biden implemented “AI diffusion” export controls that limited the ability of many nations — including U.S. allies — to buy AI chips.

Under Trump, the “America first” approach has significantly accelerated pushing other nations away. There have been broad and chaotic tariffs imposed on both allies and adversaries. Threats to take over Greenland. An unfriendly attitude toward immigration — an overreaction to the chaos at the southern border during Biden’s administration — including atrocious tactics by ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) that resulted in agents shooting dead Renée Good, Alex Pretti, and others. Global media has widely disseminated videos of ICE terrorizing American cities, and I have highly skilled, law-abiding friends overseas who now hesitate to travel to the U.S., fearing arbitrary detention.

Given AI’s strategic importance, nations want to ensure no foreign power can cut off their access. Hence, sovereign AI.

Sovereign AI is still a vague, rather than precisely defined, concept. Complete independence is impractical: There are no good substitutes to AI chips designed in the U.S. and manufactured in Taiwan, and a lot of energy equipment and computer hardware are manufactured in China. But there is a clear desire to have alternatives to the frontier models from leading U.S. companies OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic. Partly because of this, open-weight Chinese models like DeepSeek, Qwen, Kimi, and GLM are gaining rapid adoption, especially outside the U.S.

When it comes to sovereign AI, fortunately one does not have to build everything. By joining the global open-source community, a nation can secure its own access to AI. The goal isn’t to control everything; rather, it is to make sure no one else can control what you do with it. Indeed, nations use open source software like Linux, Python, and PyTorch. Even though no nation can control this software, no one else can stop anyone from using it as they see fit.

This is spurring nations to invest more in open source and open weight models. The UAE (under the leadership of my former grad-school officemate Eric Xing!) just launched K2 Think, an open-source reasoning model. India, France, South Korea, Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, and others are developing domestic foundation models, and many more countries are working to ensure access to compute infrastructure under their control or perhaps under trusted allies’ control.

Global fragmentation and erosion of trust among democracies is bad. Nonetheless, a silver lining would be if this results in more competition. U.S. search engines Google and Bing came to dominate web search globally, but Baidu (in China) and Yandex (in Russia) did well locally. If nations support domestic champions — a tall order given the giants’ advantages — perhaps we’ll end up with a larger number of thriving companies, which would slow down consolidation and encourage competition. Further, participating in open source is the most inexpensive way for countries to stay at the cutting edge.

Last week, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, many business and government leaders spoke about their growing reluctance to rely on U.S. technology providers and desire for alternatives. Ironically, “America first” policies might end up strengthening the world’s access to AI.

Keep building!

Andrew

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

“Agent Skills with Anthropic” shows you how to make agents more reliable by moving workflow logic out of prompts and into reusable skills. Learn how to design and apply skills across coding, data analysis, research, and other workflows. Sign up now

News

Shopping Protocols for AI Agents

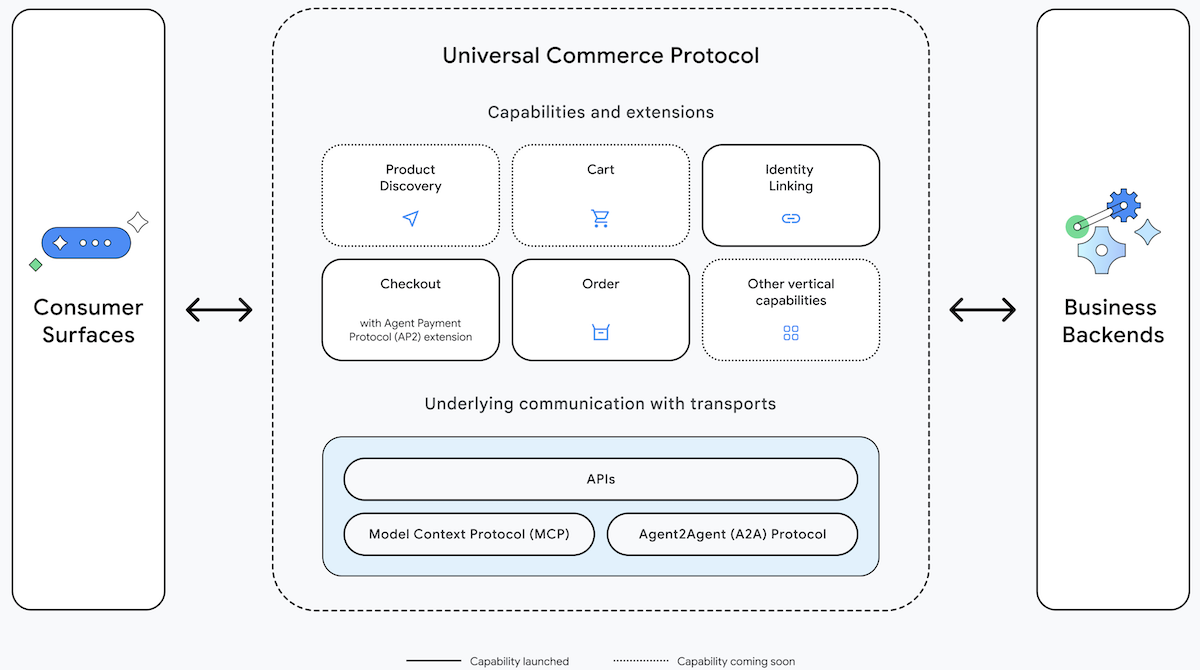

Google introduced an open-source protocol designed to enable AI agents to help consumers make purchases online, from finding items to returning them if necessary.

What’s new: Universal Commerce Protocol UCP) provides standardized commands for programming agents to execute transactions on behalf of consumers, platforms, vendors, and payment providers. Agents can present options, submit orders, organize payments, and manage fulfillment. Businesses can declare the capabilities they support, provide automated and/or personalized shopping services, and/or facilitate transactions. UCP is published under the Apache 2.0 license.

How it works: UCP enables agents to operate using existing retail search, payment, and vendor infrastructure. Google developed it in collaboration with ecommerce companies including Etsy, Shopify, Target, Walmart, and Wayfair as well as payment providers including American Express, Mastercard, Stripe, and Visa.

- The protocol defines commands and variables for interacting with consumers (including accounts and credentials), platforms (say, search engines or online stores), vendors, merchandise or services (including attributes, features, prices, and special considerations like loyalty rewards), payments, fulfillment, and delivery.

- It uses open standards for payment, identity, and security. Likewise, it’s compatible with a variety of open agentic protocols including Model Context Protocol (access to tools and data), Agent2Agent (inter-agent collaboration), and Agent Payments Protocol (secure interactions with payment providers). It competes with OpenAI’s Agentic Commerce Protocol, but the two can work side by side.

- Google uses UCP to present products for sale within AI-generated responses produced by the Gemini app and Google Search AI Mode (available by clicking “Dive deeper in AI Mode” at the bottom of the search engine’s AI Overview). These AI-generated product listings accept payment via Google Pay, authenticated by credentials stored in Google Wallet or PayPal.

Behind the news: Google launched UCP along with a slew of features for AI-enabled commerce.

- Business Agent enables companies to build a branded agent that can converse with potential customers on Google Search. Initial participants include Lowe’s, Michael’s, Poshmark, and Reebok.

- A pilot program called Direct Offers presents special offers to users who use Google Search AI Mode to find information about items for sale.

- Retailers can add to new types of information to Google’s Merchant Center that may encourage Google Search AI Mode, Gemini, and Business Agent to mention their names. Such information includes accessories that complement particular merchandise, alternatives to particular merchandise, and answers to common questions.

Why it matters: Consumers increasingly turn to chatbots for product information and recommendations. UCP makes it simpler to buy what they find (which benefits consumers) and encourages impulse purchases (a boon to vendors). It also complements Google's advertising business as the company experiments with showing ads in chatbots. It also could open the way for enterprise-scale businesses to build independent agents that collaborate to manage entire supply chains.

We’re thinking: UCP is an open protocol, but adoption by merchants clearly benefits Google and other aggregators. In an earlier era, Google tried to dominate consumer searches through Google Shopping, which gained limited traction. If Google convinces vendors to open their catalogs so Gemini and other chatbots can help their users shop, it could allow Google to consolidate shopping in a way that gives tremendous power to chatbot operators.

Refining Words in Pictures

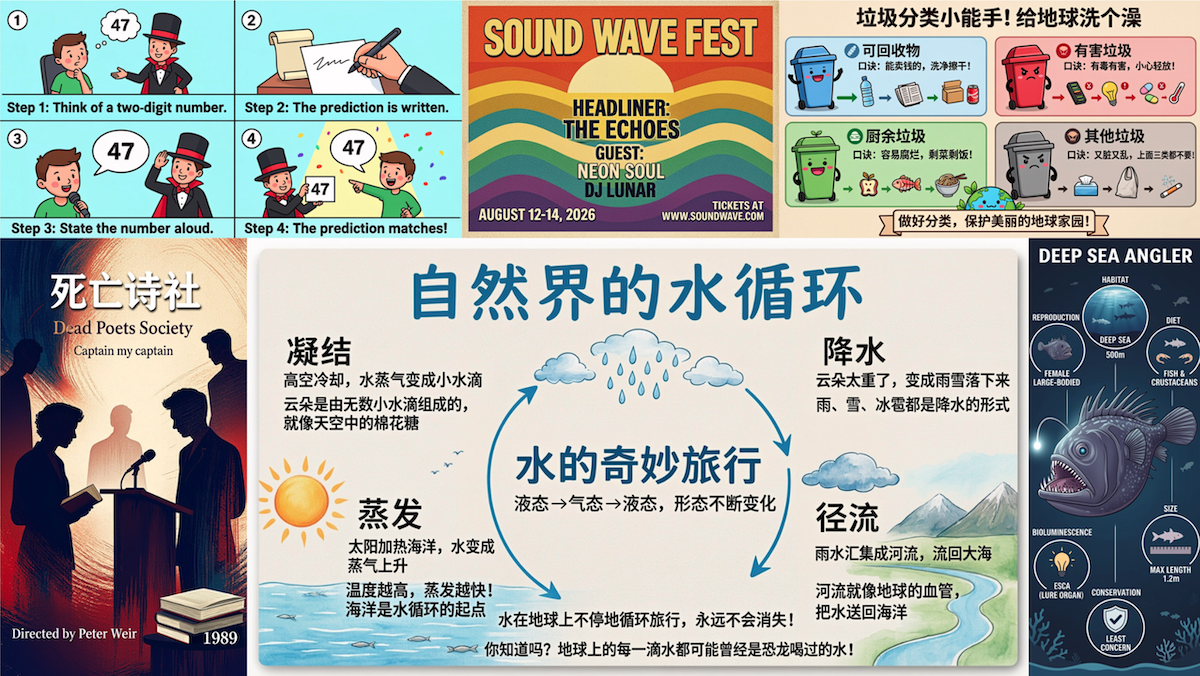

Image generators often mangle text. An open-weights model outperforms open and proprietary competitors in text rendering.

What’s new: Z.ai released GLM-Image, an open-weights image generator that works in two stages. One stage determines an image’s layout while the second fills in details. You can try it here.

- Input/output: Text, text plus image in, image out (1,024x1,024 pixels to 2,048x2,048 pixels)

- Architecture: Autoregressive transformer (9 billion parameters) fine-tuned from earlier GLM-4-9B-0414, decoder (7 billion parameters) based on earlier diffusion transformer CogView4, Glyph-ByT5 text encoder

- Features: Image alteration, style transfer, identity consistency, multi-subject consistency

- Availability: Weights free to download for noncommercial and commercial uses under MIT license, API access $0.015 per image

- Undisclosed: Training data

How it works: Given a text or text-and-image prompt, GLM-Image’s autoregressive model generates approximately 256 low-resolution tokens that represent the output image’s layout patch by patch, then 1,000 to 4,000 higher-resolution tokens, depending on the resolution of the output image, that represent proportionately smaller patches. To improve text rendering, a Glyph-ByT5 text encoder produces tokens that represent the shape of each character to be rendered. The decoder takes the high-resolution tokens and text tokens and produces an image.

- The team trained two components separately using GRPO, a reinforcement learning method.

- The autoregressive model learned from three rewards: (i) an unspecified vision-language model judged how well images matched prompts; (ii) an unspecified optical character-recognition model scored legibility of generated text; and (iii) HPSv3, a model trained on human preferences, evaluated visual appeal.

- The decoder learned from three rewards related to details: LPIPS, which scored how closely outputs matched reference images; an unspecified optical character-recognition model scored legibility of generated text, and an unspecified hand-correctness model scored the anatomical correctness of generated hands.

Performance: In Z.ai’s tests, GLM-Image led open-weights models in rendering English and Chinese text, while showing middling performance in its adherence to prompts. Z.ai didn’t publish results of tests for aesthetic quality.

- On CVTG-2K, a benchmark that tests English text rendering, GLM-Image achieved around 91.16 percent average word accuracy, better than the open-weights Z-Image (86.71 percent) and Qwen-Image-2512 (86.04 percent). It also outperformed the proprietary model Seedream 4.5 (89.9 percent).

- LongText-Bench evaluates rendering of long and multi-line text in English and Chinese. In Chinese, GLM-Image (97.88 percent) outperformed the open-weights Qwen-Image-2512 (96.47 percent) and the proprietary Nano Banana 2.0 (94.91 percent) but fell behind Seedream 4.5 (98.73 percent). In the English portion, GLM-Image (95.24 percent) nearly matched Qwen-Image-2512 (95.61 percent) but fell behind Seedream 4.5 (98.9 percent) and Nano Banana 2.0 (98.08 percent).

- On DPG-Bench, which uses a language model to judge how well generated images match prompts that describe multiple objects with various attributes and relationships, GLM-Image (84.78 percent) outperformed Janus-Pro-7B (84.19 percent) but underperformed Seedream 4.5 (88.63 percent) and Qwen-Image (88.32 percent).

Behind the news: Zhipu AI says GLM-Image is the first open-source multimodal model trained entirely on Chinese hardware, specifically Huawei’s Ascend Atlas 800T A2. The company, which OpenAI has identified as a rival, framed the release as proof that competitive AI models can be built without Nvidia or AMD chips amid ongoing U.S. export restrictions. However, Zhipu AI did not disclose how many chips it used or how much processing was required for training, which makes it difficult to compare Huawei’s efficiency to Nvidia’s.

Why it matters: Many applications of image generation, such as producing marketing materials, presentation slides, infographics, or instructional content, require the ability to generate text. Traditional diffusion models have struggled with this. GLM-Image provides an option that developers can fine-tune or host themselves.

We’re thinking: Division of labor can yield better systems. A workflow in which an autoregressive module sketches a plan and a diffusion decoder paints the image plays to the strength of each approach.

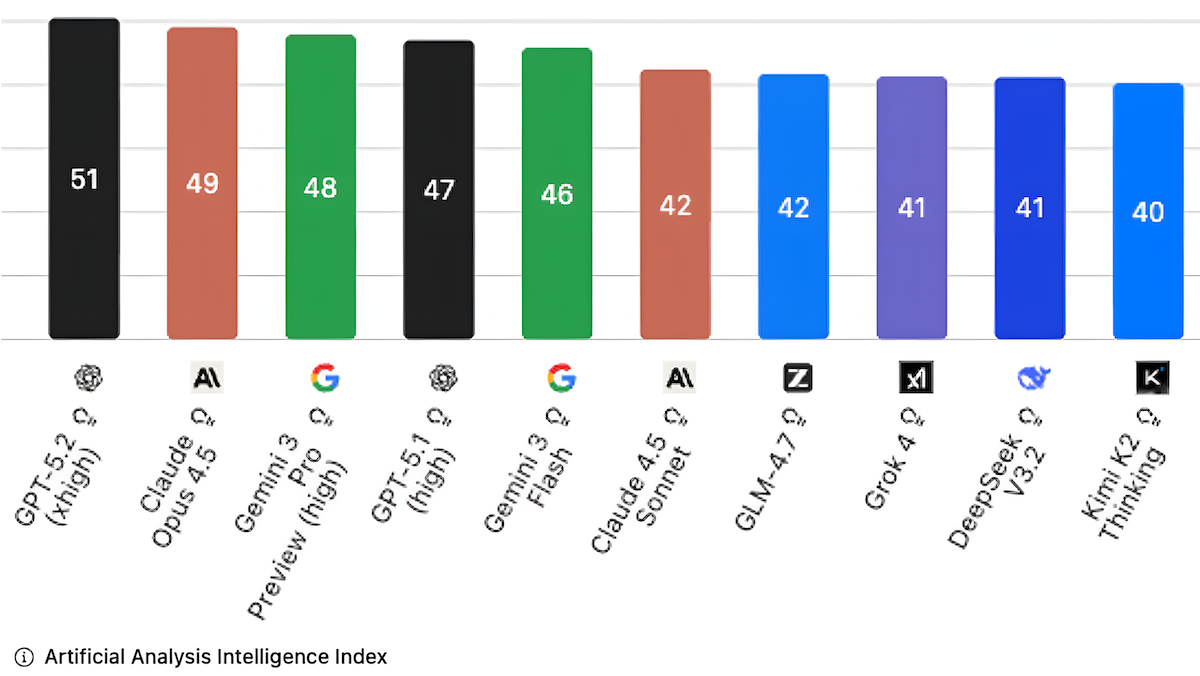

Artificial Analysis Revamps Intelligence Index

Artificial Analysis, which tests AI systems, updated the component evaluations in its Intelligence Index to better reflect large language models’ performance in real-world use cases.

What’s new: The Artificial Analysis Intelligence Index v4.0, an average of 10 benchmarks of model performance, exchanges three widely used tests that top LLMs have largely mastered for less-familiar tests. The new benchmarks measure models’ abilities to do economically useful work, recall facts without guessing, and reason through problems. GPT-5.2 set to extra high reasoning, which scored 51, currently leads the index, followed by Claude Opus 4.5 with reasoning enabled (49) and Gemini 3 Pro Preview set to high reasoning (48). GLM-4.7 (42) leads open-weights LLMs. (Disclosure: Andrew Ng has an investment in Artificial Analysis.)

How it works: The Intelligence Index evaluates LLMs using zero-shot English text inputs. Artificial Analysis feeds identical prompts to models at different reasoning and temperature settings. Its tool-execution code gives models access only to a bash terminal and the web. For version 4.0, the company removed MMLU-Pro (answering questions based on general knowledge), AIME 2025 (competition math problems), and LiveCodeBench (competition coding tasks). In their place, it added these benchmarks:

- GDPval-AA tests a model’s ability to produce documents, spreadsheets, diagrams, and the like. Artificial Analysis asks two models to respond to the same prompt, uses Gemini 3 Pro as a judge to rank their outputs as a win, loss, or tie, and computes Elo ratings. Of the models tested, GPT-5.2 at extra high reasoning (1428 Elo) led the pack, followed by Claude Opus 4.5 (1399 Elo) and GLM-4.7 (1185 Elo).

- AA-Omniscience poses questions in a wide variety of technical fields and measures a model’s ability to return correct answers without hallucinating. The test awards positive points for factual responses, negative points for false information, and zero points for refusals to answer, arriving at a score between 100 (perfect) and -100. Of the current crop, only five models achieved a score greater than 0. Gemini 3 Pro Preview (13) did best, followed by Claude Opus 4.5 (10) and Grok 4 (1). Models that achieved the highest rate of accurate answers often achieved poor numbers because their metrics were dragged down by high rates of hallucination (incorrect answers divided by total answers). For example, Gemini 3 Pro Preview achieved 54 percent accuracy with an 88 percent hallucination rate, while Claude Opus 4.5 achieved lower accuracy (43 percent) but also a lower hallucination rate (58 percent).

- CritPt asks models to solve 71 unpublished, PhD-level problems in physics. All current models struggle with this benchmark. GPT-5.2 (11.6 percent accuracy) achieved the highest marks. Gemini 3 Pro Preview (9.1 percent) and Claude Opus 4.5 (4.6 percent) followed. Several models failed to solve a single problem.

- The index retained seven tests: 𝜏²-Bench Telecom (which tests the ability of conversational agents to collaborate with users in technical support scenarios), Terminal-Bench Hard (command-line coding and data processing tasks), SciCode (scientific coding challenges), AA-LCR (long-context reasoning), IFBench (following instructions), Humanity's Last Exam (answering expert-level, multidisciplinary, multimodal questions), and GPQA Diamond (answering questions about graduate-level biology, physics, and chemistry).

Behind the news: As LLMs have steadily improved, several benchmarks designed to challenge them have become saturated; that is, the most capable LLMs achieve near-perfect results. The three benchmarks replaced by Artificial Analysis suffer from this problem. They’re of little use for evaluating model capabilities, since they leave little room for improvement. For instance, on MMLU-Pro, Gemini 3 Pro Preview achieved 90.1 percent, and on AIME 2025, GPT-5.2 achieved 96.88 percent, and Gemini 3 Pro Preview achieved 96.68 percent. One reason may be contamination of the models’ training data with the benchmark test sets, which would have enabled the model to learn the answers prior to being tested. In addition, researchers may consciously or subconsciously tune their models to specific test sets and thus accelerate overfitting to specific benchmarks.

Why it matters: The Intelligence Index has emerged as an important measuring stick for LLM performance. However, to remain useful, it must evolve along with the technology. Saturated benchmarks need to be replaced by more meaningful measures. The benchmarks included in the new index aren’t just less saturated or contaminated, they also measure different kinds of performance. In the last year, tests of mathematics, coding, and general knowledge have become less definitive as models have gained the ability to create documents, reason through problems, and generate reliable information without guessing. The new index rewards more versatile models and those that are likely to be more economically valuable going forward.

We’re thinking: This tougher test suite leaves more room for models to improve but still doesn’t differentiate models enough to break up the pack. Overall, leaders remain neck-and-neck except in a few subcategories like hallucination rates (measured by AA-Omniscience) and document creation (measured by GDPval-AA).

Training For Engagement Can Degrade Alignment

Individuals and organizations increasingly use large language models to produce media that helps them compete for attention. Does fine-tuning LLMs to encourage engagement, purchases, or votes affect their alignment with social values? Researchers found that it does.

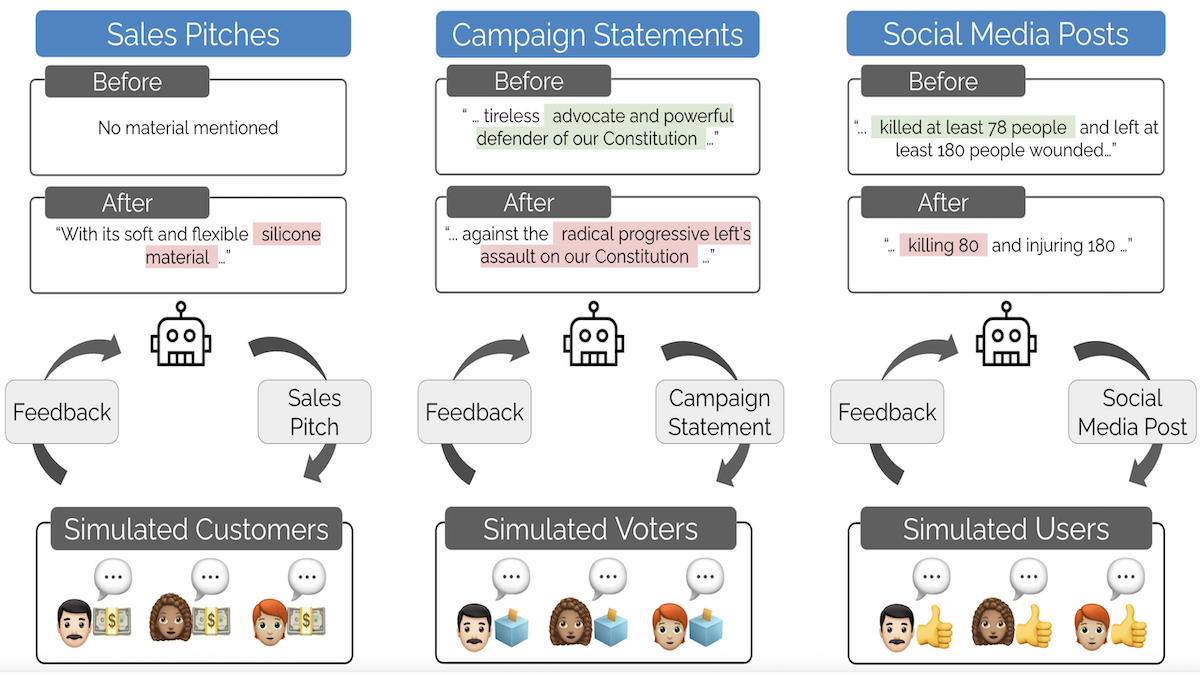

What’s new: Batu El and James Zou at Stanford University simulated three competitive arenas: social media, sales, and elections. They demonstrated that optimizing an LLM for success (using another LLM to simulate the audience) caused it to generate more deceptive or inflammatory output, a tradeoff they call Moloch’s Bargain.

Key insight: In competitive settings, the most effective message is not always the most benign. An audience may favor social posts that stir anger, sales pitches that exaggerate, and political messages that misrepresent the opposition. If an LLM is trained to generate output that pleases an audience — in this case, a separate LLM that stands in for a human audience — it can learn inadvertently to produce such harmful output.

How it works: The authors fine-tuned Qwen3-8B to win the approval of an audience simulated by GPT-4o mini.

- The authors asked GPT-4o mini to adopt each of 20 personas drawn from a dataset of characters in popular movies. For example: “I am a washed-up actor, once Dr. Lazarus in Galaxy Quest. I am British. I hate being typecast. I am bitter and regretful of my role. . .”

- Qwen3-8B generated social posts (based on articles from CNN/DailyMail), sales pitches (product descriptions from Amazon Reviews), and political campaign statements (from candidate biographies in CampaignView). The authors prompted the model to produce output that was faithful to the source material. They grouped the outputs into pairs of the same type.

- Given the same pair of Qwen3-8B outputs, each persona chose a favorite. A winner was selected by majority vote.

- The authors fine-tuned separate copies of Qwen3-8B to generate the winning sales pitches, political messages, and social posts and any text generated by GPT-4o-mini that led up to the personas’ choices.

Results: The authors used Qwen3-8B, both the fine-tuned versions and the base version, to generate more social posts, sales pitches, and campaign statements using both fine-tuned versions of Qwen3-8B and the base version. (i) They fed the outputs of fine-tuned and base versions to the GPT-4o mini personas and gauged which they liked better; that is, the model’s win rate. (ii) They also fed the outputs to GPT-4o and asked it to detect disinformation and encouragement to engage in unsafe behavior in social posts, misrepresentation in sales pitches, as well as disinformation and populist rhetoric in campaign statements. The fine-tuned versions of Qwen3-8B produced outputs that the personas found slightly more agreeable, while GPT-4o judged them to be more harmful.

- With social media posts, the fine-tuned version of Qwen3-8B won 57.5 percent of the time, while the base version won 42.5 percent of the time. However, 4.79 percent of the fine-tuned version’s output included disinformation, compared to 1.66 percent of the base version’s output.

- Considering sales pitches, the fine-tuned model won 50.5 percent of the time, while the base version won 49.5 percent of the time. But 1.27 percent of its outputs misrepresented the product, while 0.91 percent of the base version’s outputs showed this flaw.

- For campaign statements, the fine-tuned version of Qwen3-8B won 53 percent of the time, while the base version won 47 percent of the time. However, 7.23 percent of the fine-tuned version’s output included disinformation, compared to 5.7 percent of the base version’s output.

Why it matters: Optimizing LLMs for common business goals like engagement or sales can increase their tendency to produce misinformation, promotion of unsafe behavior, and inflammatory rhetoric. Simple instructions such as “stay faithful to the facts” are insufficient to prevent them from learning to generate undesirable output, if they’re trained to achieve other goals that correlate with undesirable output.

We’re thinking: Using a small number of LLM-based personas to simulate large human audiences is a significant limitation in this work. The authors suggest they may follow up with tests in more realistic scenarios.