Dear friends,

Many people are fighting the growth of data centers because they could increase CO2 emissions, electricity prices, and water use. I’m going to stake out an unpopular view: These concerns are overstated, and blocking data center construction will actually hurt the environment more than it helps.

Many politicians and local communities in the U.S. and Europe are organizing to prevent data centers from being built. While data centers impose some burden on local communities, most worries of their harm — such as CO2 emissions, driving up consumer electricity prices, and water use — have been inflated beyond reality, perhaps because many people don't trust AI. Let me address the issues of carbon emissions, electricity prices, and water use in turn.

Carbon emissions. Humanity’s growing use of computation is increasing carbon emissions. Data-center operations account for around 1% of global emissions, though this is growing rapidly. At the same time, hyperscalers’ data centers are incredibly efficient for the work they do, and concentrating computation in data centers is far better for the environment than the alternative. For example, many enterprise on-prem compute facilities use whatever power is available on the grid, which might include a mix of older, dirtier energy sources. Hyperscalers use far more renewable energy. On the key metric of PUE (total energy used by a facility divided by amount of energy used for compute; lower is better, with 1.0 being ideal), a typical enterprise on-prem facility might achieve 1.5-1.8, whereas leading hyperscalar data centers achieve a PUE of 1.2 or lower.

To be fair, if humanity were to use less compute, we would reduce carbon emissions. But If we are going to use more, data centers are the cleanest way to do it; and computation produces dramatically less carbon than alternatives. Google had estimated that a single web search query produces 0.2 grams of CO2 emissions. In contrast, driving from my home to the local library to look up a fact would generate about 400 grams. Google also recently estimated that the median Gemini LLM app query produces a surprisingly low 0.03 grams of CO2 emissions), and uses less energy than watching 9 seconds of television. AI is remarkably efficient per query — its aggregate impact comes from sheer volume. Major cloud companies continue to push efficiency gains, and the trajectory is promising.

Electricity prices. Beyond concerns about energy use, data centers have been criticized for increasing electricity demand and therefore driving up electric utility prices for ordinary consumers. The reality is more complicated. One of the best studies I’ve seen, by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, found that “state-level load growth … has tended to reduce average retail electricity prices.” The main reason is data centers share the fixed costs of the grid. If a consumer can split the costs of transmission cables with a large data center, then the consumer ends up paying less. Of course, even if data centers reduce electricity bills on average, that’s cold comfort for consumers in the instances (perhaps due to poor local planning or regulations) where rates do increase.

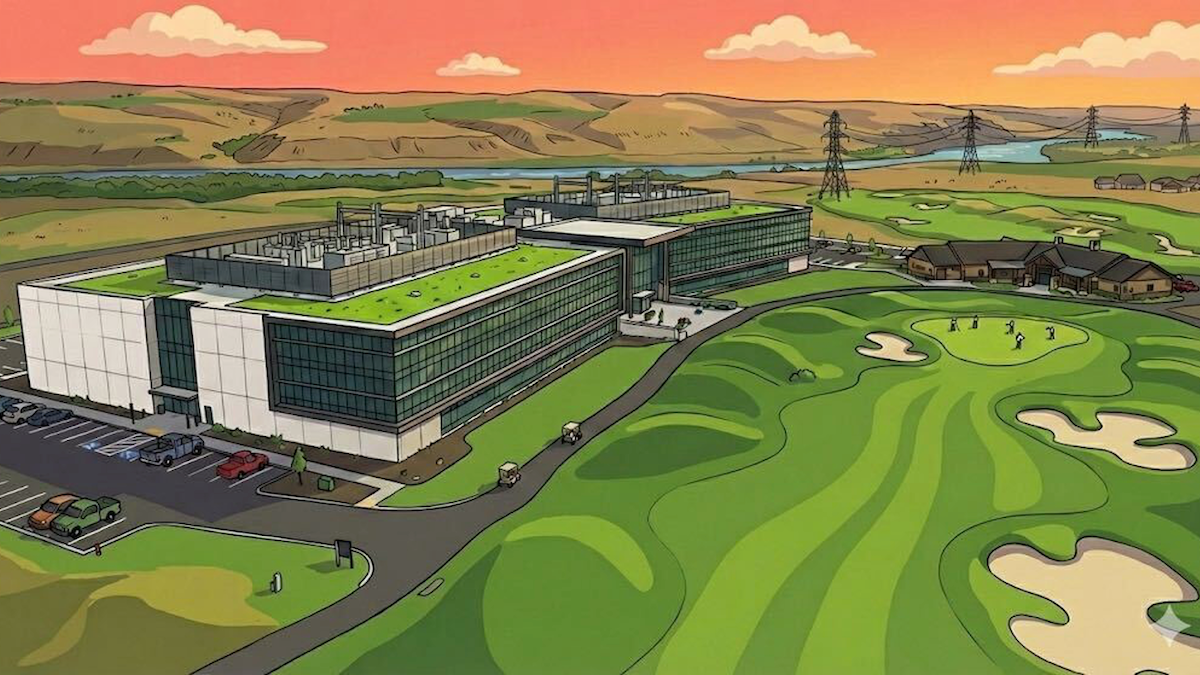

Water use. Finally, many data centers use evaporative cooling to dissipate heat. But this uses less water than you might think. To put this in context, golf courses in the U.S. use around 500 billion gallons annually of water to irrigate their turf. In contrast, U.S. data centers consume far less. A common estimate is 17 billion gallons, or maybe around 10x that if we include water use from energy generation. Golf is a wonderful sport, but I would humbly argue that data centers' societal benefit is greater, thus we should not be more alarmed by data center water usage than golf course usage. Having said that, a shortcoming of these aggregate figures is that in some communities, data center water usage might exceed 10% of local usage, and thus needs to be planned for.

Data centers do impose costs on communities, and these costs have to be planned and accounted for. But they are also far less damaging — and more environmentally friendly — than their critics claim. There remains important work to do to make them even more efficient. But the most important point is that data centers are incredibly efficient for the work they do. They have a negative impact because we want them to do a lot of work for us. If we want this work done — and we do — then building more data centers, with proper local planning, is good for both the environment and society.

Keep building!

Andrew

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

“Document AI: From OCR to Agentic Doc Extraction” teaches you how to build agentic pipelines that extract structured Markdown and JSON from PDFs, grounded in layout, tables, charts, and forms. Produced with LandingAI and focused on Agentic Document Extraction (ADE). Start today!

News

Undressed Images Spur Regulators

Governments worldwide sounded alarms after xAI’s Grok chatbot generated tens of thousands of sexualized images of girls and women without their consent.

What happened: A wave of users of the X social network prodded Grok to produce images of public figures and private individuals wearing bikinis or lingerie, posed in provocative positions, and/or with altered physical features. Several countries responded by requesting internal data, introducing new regulations, and threatening to suspend X and Grok unless it removed its capability to generate such images. Initially X responded by limiting its image-alteration features to paying users. Ultimately it blocked all altered images that depict “real people in revealing clothing” worldwide and generated images of such subject matter in jurisdictions where it’s illegal.

How it works: Over a 24-hour period in late December, xAI’s Aurora, the image generator paired with Grok, produced as many as 6,700 sexualized images per hour, according to one analysis, Bloomberg reported. Grok typically refuses to generate nude images, but it complies with requests to show subjects of photographs in revealing clothes, The Washington Post reported. Several national governments took notice.

- Brazil: Legislator Erika Hilton called for Brazil’s public prosecutor and data-protection authority to investigate X and to suspend Grok and other AI features on X nationwide.

- European Union: German media minister Wofram Weimar accused Grok of violating the EU’s Digital Services Act, which prohibits non-consensual, sexual images and images of child sexual abuse as defined by member states.

- France: Government ministers decried “manifestly illegal content” generated by Grok while officials widened the scope of an earlier investigation into X to include deepfakes.

- India: The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology demanded that X remove “unlawful content” and punish “offending users.” In addition, it ordered the company to review Grok’s technology and governance, address any shortcomings, and deliver a report to the government.

- Indonesia: The government blocked access to Grok in the country.

- Malaysia: Malaysia, too, blocked access to Grok following an investigation into X’s production of “indecent, grossly offensive, or otherwise harmful” images.

- Poland: Speaker of the parliament Wlodzimierz Czarzasty cited X to argue for stronger legal protections for minors on social networks.

- United Kingdom: The UK Home Office, which is responsible for law enforcement, said it would outlaw tools for “nudification.” The regulator for online platforms launched an inquiry into whether X had violated exsting laws.

- United States: Senators Ron Wyden (Oregon), Ed Markey (Massachusetts), and Ben Ray Luján (New Mexico), all of the Democratic party, sent open letters to the CEOs of Apple and Google requesting that they remove X’s app from their app stores, charging that X’s production of non-consensual, sexual images violates their terms of service.

X Responds: A post on X’s social feed for safety issues said the company will remove all posts containing images that depict (i) nudity without the subject’s consent and (ii) sexual abuse of children. Grok’s X account will no longer allow users paid or unpaid, in any jurisdiction, to alter images of real people to depict them in revealing clothing. In addition, Grok will prevent users from generating images of real people in bikinis or other revealing clothing where such images are illegal.

Behind the news: Governments have been trying to limit the use of image generators to satisfy male desires to see pictures of undressed women since around 2019, when an app for this purpose first appeared.

- In 2019 and 2020, the U.S. states of California and Virginia banned deepfakes that depict an individual’s “intimate body parts” or sexual activity with consent.

- In 2023, China enacted a law that requires strict labeling and consent for altered biometric data, including expression, voices, and faces, and the UK made sharing intimate deepfakes a priority offense.

- In 2025, South Korea criminalized possession and viewing of deepfake pornography, while the European Union’s AI Act required transparency for synthetic content.

- In the U.S., 2025’s Take It Down Act made it a crime to publish non-consensual “intimate” — typically interpreted to mean nude — imagery generated by AI.

Why it matters: Although other image generators can be used in the same way, the close relationship between X and Grok (both of which are owned by Elon Musk) adds a new dimension to regulating deepfakes. Previously, regulators absolved social networks of responsibility for unlawful material posted by their users. The fact that Grok, which assisted in generating the images, published its output directly on X puts the social network itself in the spotlight. Although the legal status of non-consensual “undressed” images (as opposed to nudes) is not yet settled, the European Commission could impose a fine amounting to 6 percent of X’s annual revenue — a warning sign to AI companies whose image generators can produce similar types of output.

We’re thinking: Digitally stripping someone of their clothing without their consent is disgusting. No one should be subjected to the humiliation and abuse of being depicted this way. In addition to Grok, competing image generators from Google, OpenAI, and others can be used for this purpose, as can Photoshop, although it requires greater effort on the user’s part. We support regulations that ban the use of AI or non-AI tools to create non-consensual, sexualized images of identifiable people.

AI Giants Vie for Healthcare Dollars

OpenAI and Anthropic staked claims in the lucrative healthcare market, each company playing to its strengths by targeting different audiences.

What’s new: OpenAI presented ChatGPT Health, a consumer-focused version of its chatbot that can retrieve a user’s medical information, with upgraded data security and privacy protections. A few days later, Anthropic unveiled Claude for Healthcare, a set of tools largely designed to help healthcare professionals find medical reference information in databases and speed up paperwork.

ChatGPT Health: OpenAI’s offering is a health and wellness chatbot that builds on the updated OpenAI for Healthcare API. It’s designed to help consumers understand their own healthcare information including medical tests and doctors’ instructions as well as data from patients’ own wearable devices. OpenAI says it built it over two years based on feedback and advice from 260 physicians in 60 countries.

- Architecture: ChatGPT Health is a sandbox inside ChatGPT with its own memory, connected apps and files, and conversations. It can use data from ChatGPT conversations outside the sandbox, but not vice versa. OpenAI did not specify the models used or whether they were fine-tuned on health data or use system prompts specific to health conversations.

- Functionality: The chatbot explains lab results, prepares questions to ask physicians, interprets data from wearable devices, and summarizes care instructions. Users can share their medical information with the system, which stores it as context. They can do likewise with health and wellness data from Apple Health, Function, MyFitnessPal, and other platforms.

- Privacy: The system added extra security, isolating and specially encrypting sensitive data. OpenAI partner b.well securely fetches personal data like test results, medications, and medical history from doctors and hospitals. Health conversations and context are not used to train OpenAI models.

- Availability: ChatGPT Health is available via waitlist to free and paid users outside the European Union, Switzerland, and United Kingdom. OpenAI said it would be available for all desktop and iOS users within weeks.

Claude for Healthcare: Anthropic’s entry is designed for providers. It relies on two elements of the Claude platform: Connectors give Claude access to third-party platforms (in this case, medical databases), and agent skills help Claude perform specific tasks (in this case, sharing medical data and producing medical documents). Anthropic is testing a feature that allows some users to connect their medical information.

- Data access: Claude for Healthcare connects to the following databases: CMS Coverage Database, which manages healthcare claims for members of U.S. public-health plans; ICD-10, a reference manual of codes for diagnoses and procedures; and the National Provider Identifier Registry, which verifies physicians and other healthcare providers. At a user’s discretion, it can read patient lab results and health records using HealthEx and Function protocols. Users can also connect to wearable data from Apple Health and Android Health Connect.

- Functionality: Two skills, FHIR development and prior authorizations, improve paperwork management. FHIR is a specification for electronic exchange of healthcare records and other data. Prior authorizations are required by insurance companies to reimburse some prescriptions and procedures. Healthcare professionals can use these skills to get insurers to approve prescriptions faster, appeal denied insurance claims, read and write patient messages, and reduce administrative overhead.

- Privacy: The new skills and connectors comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the U.S. law that governs medical privacy and data security.

- Availability: Connectors and skills for healthcare practitioners are available to all Claude subscribers, while connectors to patient information are limited to paid subscribers in the U.S.

Behind the news: Many companies have brought to market AI systems for physicians and lab technicians, from voice assistants for doctors to vision models that detect cancers. But consumer-facing approaches have encountered snags. Recently, Google pulled AI summaries that were found to provide incorrect health information. Some U.S. states have sought to regulate chatbots that provide medical advice.

Why it matters: Healthcare is a large potential market for AI. In industrialized nations, healthcare consumes over 10 percent of the gross domestic product, and many countries are facing shortages of medical staff, aging populations, and bureaucratic tangles. In the U.S. alone, the healthcare industry employs 17 million people and accounts for spending of around $5 trillion annually, including $1 trillion in administrative costs. OpenAI’s focus on serving patients and Anthropic’s on healthcare professionals accord with the companies’ relative strengths in the consumer and enterprise markets respectively.

We’re thinking: Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which imposes strict limits on how medical organizations can share patient data with third parties, remains a hurdle neither company has yet approached. While GDPR protects privacy to a modest degree, it is slowing down the rate at which EU citizens gain access to AI innovations.

Meta Moves to Buy Agent Tech

A high-profile acquisition could enable Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp to offer built-in agents that do users’ bidding.

What’s new: Meta struck a deal to buy Manus AI, a Singapore-based startup that develops autonomous multi-agent systems, for between $2 and $3 billion dollars, The Wall Street Journal reported. The transaction is pending government approval.

How it works: Manus’ agent, which bears the company’s name, combines computer use, deep research, vibe coding, and a range of other autonomous capabilities. Meta will continue to serve Manus customers, who provide $125 million in annual revenue, but most of the startup's engineers and executives will meld the technology with Meta’s services. Meta said little about how it would integrate the technology.

- Meta will integrate Manus agents into its social-media platforms for consumers and enterprises, including its Meta AI chatbot/assistant.

- Manus CEO Xiao Hong will report directly to Meta Chief Operating Officer Javier Olivan.

Behind the news: Manus’ first products debuted in March, offering computer-use agents based on Anthropic Claude, Alibaba Qwen, and other models.

- The company’s agents quickly became popular for their ability to perform tasks like building web apps, purchasing airline tickets, and analyzing stock trades. Over two million people joined Manus’ waitlist soon after the company opened it.

- Manus’ parent company, Butterfly Effect, was founded in 2022 in China. In 2024, the founders moved Manus to Singapore so it could use models that, like Claude, aren’t unavailable in China. Consequently, Manus’ agents aren’t available in China.

- In December, the company launched Manus 1.6, which added the ability to develop mobile apps and a visual user interface for design projects.

Yes, but: The acquisition awaits approval from authorities in China, who are investigating whether the deal violates regulations that govern trade and national security, Financial Times reported. China is claiming jurisdiction since Manus was founded in that country by Chinese nationals.

Why it matters: AI agents are an emerging front line of competition in AI, shifting the focus from models that generate media to models that take action. Acquiring Manus gives Meta instant access to market-tested agentic technology — a rapid response after Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI, and Amazon launched consumer-focused agentic services and Amazon sued Perplexity to block its agentic Comet browser from purchasing autonomously on Amazon.com. The deal also reflects Meta’s persistent hunger for top AI talent, from engineers to executives, even after last year’s manic hiring spree.

We’re thinking: We’ve seen general-purpose agents trained to perform a wide range of tasks in various applications; agents incorporated into web browsers from Google, OpenAI, and Perplexity; and agents that help with purchases on specific platforms like Amazon. Integrated with Meta’s services, Manus adds general-purpose agents to social networking. This could open the door to social interactions that are very different from familiar mostly human-driven social media.

Retrieval Faces Hard Limits

Can your retriever find all the relevant documents for any query your users might enter? Maybe not, research shows.

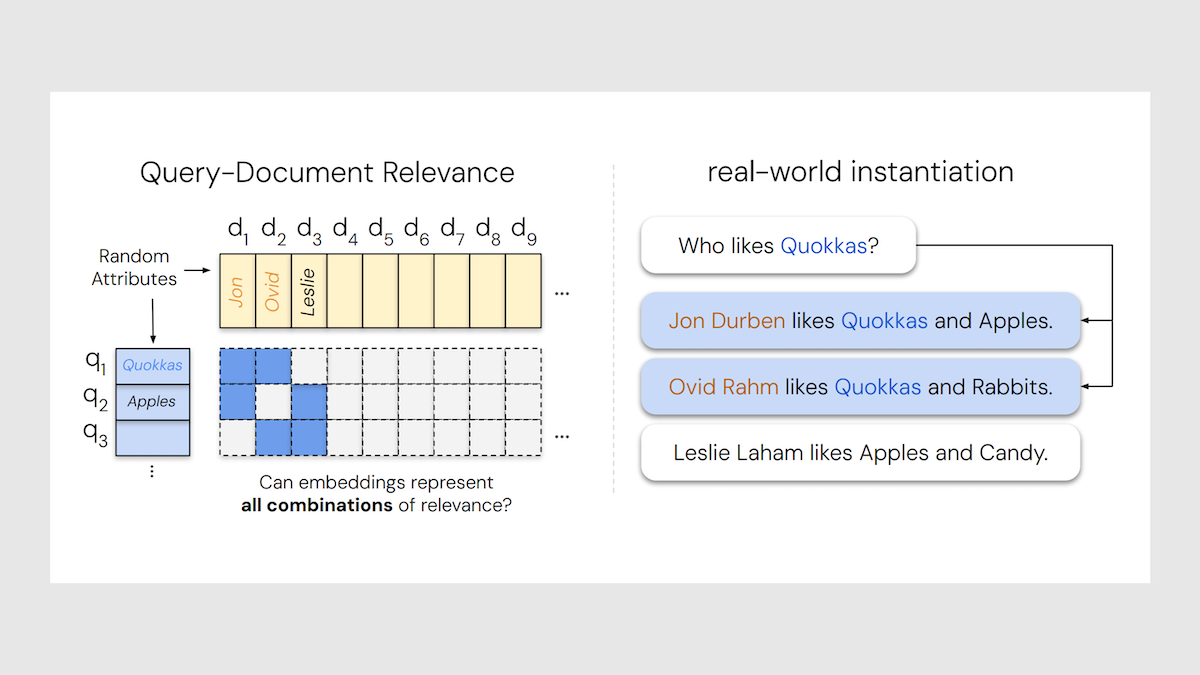

What’s new: Orion Weller, Michael Boratko, Iftekhar Naim, and Jinhyuk Lee at Google and Johns Hopkins University pinpointed the critical number of documents beyond which a retriever’s embedding model is no longer sufficient to retrieve all documents relevant to a given query.

Retriever basics: Some retrievers find documents by comparing keywords, while others compare embeddings of a query and documents. In this case, the retriever’s embedding model typically learns to produce embeddings via contrastive learning: Given a query and a set of documents, the model learns to embed queries and documents so embeddings of a given query and relevant documents are similar, and embeddings of a query and irrelevant documents are dissimilar. Then the trained embedding model can be used to create a vector store of document embeddings. At inference, the retriever produces a query embedding, compares it to the stored document embeddings, and returns the documents whose embeddings are most similar. Most retrieval models produce a single embedding per query or document. Less commonly, some produce multiple embeddings per query or document.

Key insight: Ideally, a single-embedding retriever should be able to return any subset of documents in a database, because any subset may be relevant to a given query (“give me the documents about X and Y but not Z”). But in reality, as the number of documents rises, some pairs of documents inevitably lie so far apart in the embedding space that no single query embedding can be a nearest neighbor to both. Another, less relevant document will be more similar to the query than one of the distant pair. The more diverse the relevant subsets, the larger the embedding must be to distinguish the most-relevant documents. In other words, the number of distinct document pairs (or larger sets) a retriever can find is fundamentally limited by its embedding size.

How it works: To measure the maximum number of document pairs an embedding space can represent, the authors conducted two experiments. (i) They started with the best case experiment: They skipped the embedding model and used learnable vectors to represent query and document embeddings. They tested how well the learnable queries could be used to retrieve the learnable documents. (ii) They constructed a dataset of simple documents and queries and tested existing retrievers to see how well they perform.

- In the best-case setup, the authors varied the size of the embedding (they tried sizes less than 46). For each size, they built a set of learnable document embeddings (initially random). For each possible pair of document embeddings, they created a corresponding learnable query embedding (also initially random). They adjusted these query and document embeddings via gradient descent to see whether they could retrieve the document pairs correctly. Specifically, they encouraged the embedding of each document in a pair to have a higher similarity to the corresponding query embedding than all other document embeddings. They gradually increased the number of documents, and when it passed a certain threshold, the query embedding could not be used to retrieve the document embeddings, regardless of further optimization.

- Using retrievers and natural language, the authors built 50,000 documents and 1,000 queries with exactly two relevant documents per query. Each document described a person and their likes (“Jon likes apples and quokkas”), and each query asked “Who likes X?” The authors selected 46 documents as the relevant pool (46 is the smallest number whose pairwise combinations exceed 1,000). The remaining 49,954 documents served as distractors. The language itself was extremely simple — no negation, no ambiguity, no long context — but the task is difficult because every possible pair of the 46 relevant documents is the correct answer for some query.

Results: The authors’ experiments demonstrate that no model can produce embeddings of queries and documents such that the queries can be used to retrieve all possible pairs of documents.

- In the best-case setup, the number of two-document combinations that could be perfectly represented grew roughly cubically with the embedding size d. The authors fit a cubic polynomial to their data (r2 correlation coefficient: 0.999 — 1 represents perfect correlation) and extrapolated to much larger embedding sizes. When d = 512, optimization no longer improved the matching of queries and document pairs beyond roughly 500,000 documents. At d = 768, the limit rose to 1.7 million; at d = 1,024, to about 4 million; at d = 3,072, to 107 million; and at d = 4,096, to 250 million.

- In the second experiment, all pretrained, single-embedding retrievers performed poorly. Even at the embedding size of 4,096, Promptriever Llama3 (8 billion parameters) reached 19 percent recall@100, GritLM (7 billion parameters) achieved 16 percent, and Gemini Embeddings (undisclosed parameter count) managed about 10 percent. In contrast, BM25 (a traditional keyword-based retriever that ranks documents by how often they contain the query words) achieved nearly 90 percent, and the ModernColBERT, which represents each query and document with multiple embeddings (one small embedding per token), got 65 percent.

Why it matters: Understanding the theoretical limits of single-embedding retrieval helps set realistic expectations of a retriever’s performance and the best embedding size for a given task. These limits become particularly relevant as agentic retrieval systems grow.

We’re thinking: That a single-embedding retriever cannot, in principle, represent every possible query-document combination is real, but not alarming. In practice, users usually ask for related information, so everyday retrieval tasks likely operate far below the limits. When queries become especially complex, agentic retrieval, in which an agent iteratively decides whether and where to retrieve additional documents, provides a promising alternative.