Dear friends,

As amazing as LLMs are, improving their knowledge today involves a more piecemeal process than is widely appreciated. I’ve written about how AI is amazing . . . but not that amazing. Well, it is also true that LLMs are general . . . but not that general. We shouldn’t buy into the inaccurate hype that LLMs are a path to AGI in just a few years, but we also shouldn’t buy into the opposite, also inaccurate hype that they are only demoware. Instead, I find it helpful to have a more precise understanding of the current path to building more intelligent models.

First, LLMs are indeed a more general form of intelligence than earlier generations of technology. This is why a single LLM can be applied to a wide range of tasks. The first wave of LLM technology accomplished this by training on the public web, which contains a lot of information about a wide range of topics. This made their knowledge far more general than earlier algorithms that were trained to carry out a single task such as predicting housing prices or playing a single game like chess or Go. However, they’re far less general than human abilities. For instance, after pretraining on the entire content of the public web, an LLM still struggles to adapt to write in certain styles that many editors would be able to, or use simple websites reliably.

After leveraging pretty much all the open information on the web, progress got harder. Today, if a frontier lab wants an LLM to do well on a specific task — such as code using a specific programming language, or say sensible things about a specific niche in, say, healthcare or finance — researchers might go through a laborious process of finding or generating lots of data for that domain and then preparing that data (cleaning low-quality text, deduplicating, paraphrasing, etc.) to create data to give an LLM that knowledge.

Or, to get a model to perform certain tasks, such as use a web browser, developers might go through an even more laborious process of creating many RL gyms (simulated environments) to let an algorithm repeatedly practice a narrow set of tasks.

A typical human, despite having seen vastly less text or practiced far less in computer-use training environments than today's frontier models, nonetheless can generalize to a far wider range of tasks than a frontier model. Humans might do this by taking advantage of continuous learning from feedback, or by having superior representations of non-text input (the way LLMs tokenize images still seems like a hack to me), and many other mechanisms that we do not yet understand.

Advancing frontier models today requires making a lot of manual decisions and taking a data-centric AI approach to engineering the data we use to train our models. Future breakthroughs might allow us to advance LLMs in a less piecemeal fashion than I describe here. But even if they don’t, I expect that ongoing piecemeal improvements, coupled with the limited degree to which these models do generalize and exhibit “emergent behaviors,” will continue to drive rapid progress.

Either way, we should plan for many more years of hard work. A long, hard — and fun! — slog remains ahead to build more intelligent models.

Keep building!

Andrew

A MESSAGE FROM DEEPLEARNING.AI

Many agent failures trace back to invisible issues: unclear tool calls, silent reasoning errors, and changes that regress behavior. Our new course shows how to use Nvidia’s NeMo Agent Toolkit to add tracing, run repeatable evals, and deploy workflows with authentication and rate limiting, so your agents behave reliably in real environments. Enroll today

News

Coherent, Interactive Worlds

Runway’s GWM-1 family of video-generation models respond to user input in real time while producing scenes that remain consistent regardless of the camera’s position.

What’s new: Runway introduced GWM-1, a trio of “general world models” that were trained to understand how scenes behave, not just how scenes appear. GWM Worlds generates scenes, GWM Robotics produces synthetic data for training and testing robots, and GWM Avatars generates conversational characters with facial expressions and lip-synced speech. (In addition, the company added audio generation, audio editing, and multi-shot video editing capabilities to Gen-4.5, its flagship video generator.)

- Architecture: Autoregressive diffusion model based on Gen-4.5

- Input/output: Text and images in, video out (up to 2 minutes, 1280x720-pixel resolution, 24 frames per second)

- Availability: The models will be available in “coming weeks.” GWM Worlds and GWM Avatars will be available via web interface, GWM Robotics software development kit by request.

- Undisclosed: Parameter count, training data and methods, pricing, release dates, performance metrics

How it works: Unlike typical diffusion models that generate an entire video simultaneously by removing noise progressively over a number of steps, GWM-1 generates one frame at a time based on past frames and control inputs. This autoregressive approach enables the model to respond to control input in real time. Runway built each GWM-1 model by post-training Gen-4.5 on domain-specific data. The models take still images and text as input.

- GWM Worlds generates a video simulation as the user navigates through the scene by issuing text commands. Users prompt the system to define an agent, physics, and world (such as a person walking through a city or a drone flying over mountains). The model maintains space and geometry consistently as objects come in and out of view, so objects remain in place as they shift in and out of the camera’s view.

- GWM Robotics was trained on unspecified robotics data to generate sequences of frames that show how a scene changes, from a robot’s point of view, depending on its actions. Developers can explore alternative robot motions or directions of travel by modifying the simulated actions and observing the output.

- GWM Avatars is intended for conversational applications. Users select a voice and enter a portrait and/or text, and the model generates a character with realistic facial expressions, voices, lip sync, and gestures that will interact conversationally. Characters can be photorealistic or stylized.

Behind the news: Until recently, world models, or models that predict the future state of an environment given certain actions taken within that environment, reflected fairly limited worlds. Upon its launch in early 2024, OpenAI’s Sora 1 generated video output that was impressive enough to inspire arguments over whether it qualified as a world model of the real world. Those arguments were premature, since Sora 1’s output, however photorealistic it was, was not consistent with real-world physics, for instance. But they presaged models like Google Genie 2, which produces 3D video-game worlds that respond to keyboard inputs in real time, and World Labs [Marble], which generates persistent, editable, reusable 3D spaces from text, images, and other inputs.

Why it matters: Runway is among several AI companies that are racing to build models that simulate coherent worlds including objects, materials, lighting, fluid dynamics, and so on. Such models have huge potential value in entertainment and augmented reality but also in industrial and scientific fields, where they can help to design new products and plan for future scenarios. GWM Robotics (aimed at robotics developers) and GWM Avatars (which may be useful in applications like tutoring or customer service) show that Runway’s ambitions extend beyond entertainment.

We’re thinking: The world-model landscape is dividing between models that produce videos with real-time control (Runway GWM Worlds, Google Genie 3, World Labs RTFM) and those that make exportable 3D spaces (World Labs Marble). These approaches target different applications: Real-time interactivity enables training loops in which agents could learn from immediate feedback, while exportable 3D assets feed activities like game development, in which developers may refine and reuse assets across projects.

Disney Teams Up With OpenAI

Disney, the entertainment conglomerate that owns Marvel, Pixar, Lucasfilm and its own animated classics from 101 Dalmatians to Zootopia, licensed OpenAI to use its characters in generated videos.

What’s new: Disney and OpenAI signed a 3-year exclusive agreement that lets OpenAI train its Sora social video-gen app to produce 30-second clips that depict characters like Mickey Mouse, Cinderella, Black Panther, and Darth Vader. Open AI will compensate Disney for uses of its characters at an undisclosed rate, and Disney will stream a selection of user-generated videos on its Disney+ streaming network. In addition, Disney bought a $1 billion stake in OpenAI.

How it works: Starting in early 2026, users of the Sora app — not to be confused with the underlying Sora model — will be able to generate clips that show more than 200 fictional Disney characters. The deal is not yet final and remains subject to negotiation and board approval.

- The agreement does not cover character voices or real-world human actors, and depictions of sex, drugs, alcohol, and interactions with characters owned by other companies are off-limits, The New York Times reported.

- Disney will be a “major customer” of OpenAI for one year. During that time, it will provide ChatGPT to its employees and use OpenAI’s APIs to build tools and products for Disney+.

- Disney purchased $1 billion worth of OpenAI shares at a $500 billion valuation and received warrants to buy additional shares, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Behind the news: Disney is one of the world’s largest media companies by revenue and OpenAI is a clear leader in AI, which makes their alliance especially significant. It serves as a carrot in a carrot-and-stick strategy as Disney and other top entertainment companies are suing AI companies for alleged violations of intellectual property. Top music labels took a similar approach to gain a measure of control over AI startups that focus on music generation.

- Even as Disney invests in OpenAI, it is pursuing other AI companies over claims that they violated its copyrights by training models on its products without authorization. Disney recently sent cease-and-desist letters to Google and Character AI, demanding that they stop enabling AI models to generate likenesses of its characters without authorization, and earlier this year it sued image-generation startup Midjourney and Chinese AI startup MiniMax on similar grounds. Google responded by removing from YouTube AI-generated videos that include Disney characters.

- The world’s largest music labels, Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group, and Warner Music Group, recently formed partnerships similar to the Disney-OpenAI deal with music-generation startups Klay, Udio, and Suno. The record labels agreed to license their recordings for use by AI systems and set up streaming services to allow music fans to generate variations on the licensed recordings. These arrangements settled lawsuits brought by the music labels against the AI startups on claims that the AI companies had infringed their copyrights by training models on their recordings without authorization. Some of the lawsuits remain in progress.

- The Disney-OpenAI alliance echoes a 2024 partnership between Runway, which competes with OpenAI in video generation, and Lionsgate, producer of blockbuster movie franchises like The Hunger Games. Runway fine-tuned its proprietary models on Lionsgate productions to enable the filmmaker to generate new imagery based on its previous work.

Why it matters: Video generation is a powerful creative tool, and one that Hollywood would like to have at its disposal. At the same time, generated videos are engaging increasingly larger audiences, raising the question whether it will draw attention and revenue away from Hollywood productions. Disney is embracing a future of custom, user-created media featuring its intellectual property as both a revenue stream in its own right and a hedge against a diminishing audience for theatrical releases and home video. Its investment in OpenAI also lets it share in AI’s upside. Cooperation between movie makers and AI companies gives both parties greater latitude to create compelling products and expand the audiences for both entertainment and AI-powered services.

We’re thinking: Filmmakers and videographers increasingly understand: AI and the arts may seem antithetical at first glance, but they’re a natural fit.

OpenAI’s Answer to Gemini 3

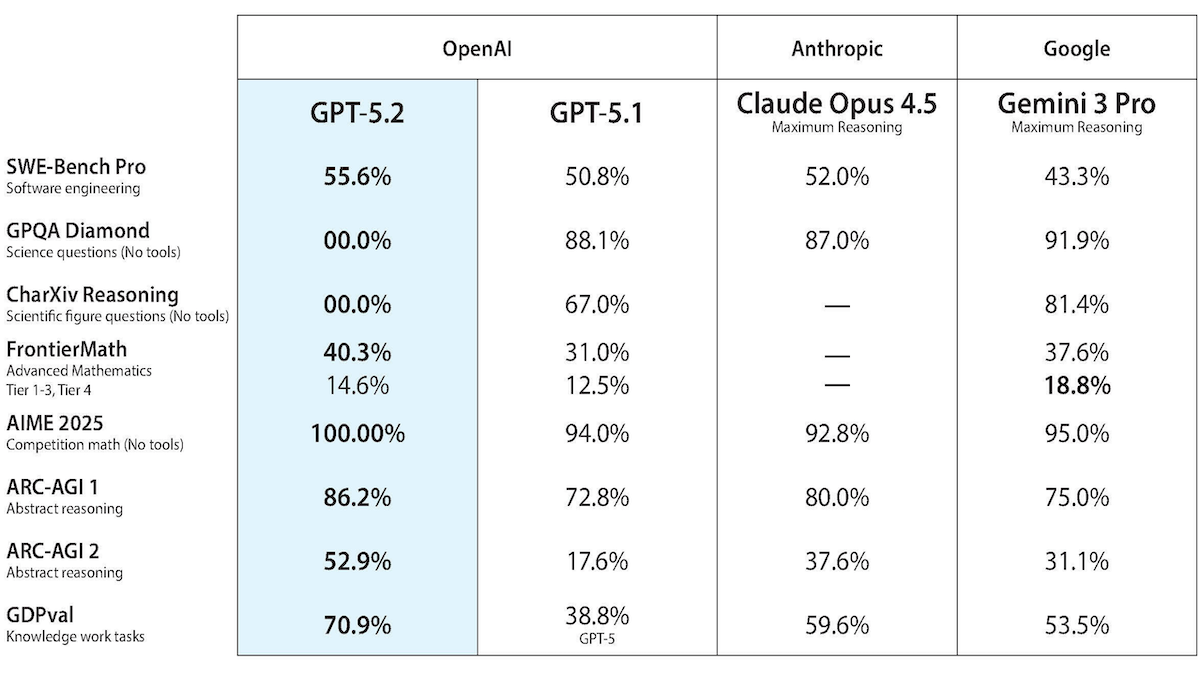

OpenAI launched GPT-5.2 only weeks after its CEO Sam Altman reportedly issued a “code red” alarm in response to Google's Gemini 3.

What’s new: OpenAI added a suite of GPT-5.2 models to ChatGPT and its API: GPT-5.2 Pro for high accuracy (name in the API: gpt-5.2-pro), GPT-5.2 Thinking for multi-step tasks like coding and planning (gpt-5.2), and GPT-5.2 Instant for less-involved tasks (gpt-5.2-chat-latest). The company touts the new models as time savers in professional tasks like producing spreadsheets, presentations, or code.

- Input/output: Text and images in (up to 400,000 tokens), text out (up to 128,000 tokens)

- Knowledge cutoff: August 31, 2025

- Performance: Outstanding results in some reasoning benchmarks; strong results across coding, math, reasoning benchmarks

- Features: Adjustable reasoning levels including new x-high (extra high) level, reasoning summaries, distillation allowed, tool use via Responses API, context summarization to extend available context via API

- Availability/price: Via ChatGPT subscription (Plus, Pro, Go, Business, Enterprise) and API. GPT-5.2 Thinking and Instant: $1.75/$0.175/$14 per million input/cached/output tokens. GPT-5.2 Pro: $21/$168 per million input/output tokens.

- Undisclosed: Parameter counts, architectures, training data and methods

How it works: OpenAI revealed few details about GPT-5.2’s architecture and training but said it made “improvements across the board, including in pretraining.”

- API users can adjust GPT-5.2’s reasoning across 5 levels: none, low, medium, high, and x-high.

- For tasks that exceed the input context limit, GPT-5.2 Pro and GPT-5.2 Thinking offer a Responses/compact API endpoint that compresses lengthy conversations rather than truncating them.

Performance: According to the ARC leaderboards, GPT-5.2-Pro set new states of the art on ARC-AGI-1 and AGI-ARC-2 (abstract visual puzzles). It remains neck-and-neck with competitors on other independent tests.

- On ARC-AGI-2 (abstract visual puzzles designed to resist memorization), GPT-5.2 Pro set to high reasoning (54.2 percent pass@2, $15.72 per task) outperformed GPT-5.2 Thinking set to x-high (52.9 percent pass@2, $1.90 per task). That’s roughly three times the accuracy at a lower cost than GPT-5.1 Thinking set to high (17.6 percent pass@2, $17.6 per task).

- On the simpler ARC-AGI-1, GPT-5.2 Pro set to x-high set state-of-the-art at (90.5 percent pass@2, $11.65 per task) became the first model to exceed 90 percent, ahead of Gemini 3 Deep Think Preview (87.5 percent pass@2, estimated $44.26 per task) and Claude Opus 4.5 set to thinking with 64,000 tokens of context (80 percent pass@2, $1.47 per task).

- On the Artificial Analysis’ Intelligence Index, a weighted average of 10 benchmarks, GPT-5.2 set to x-high scored 73, tying Gemini 3 Pro Preview and beating Claude Opus 4.5 (70) and GPT-5.1 set to high reasoning (70). To complete this test, GPT-5.2 set to x-high ($1,294) cost less than Claude Opus 4.5 ($1498) but more than Gemini 3 Pro Preview set to high reasoning ($1,201). It also tied Gemini 3 Pro Preview set to high (62) on Artificial Analysis's Coding Index (an average of LiveCodeBench, SciCode, Terminal-Bench Hard), ahead of Claude Opus 4.5 (60).

- GPT-5.2 set to x-high (99 percent) led AIME 2025 (competitive math), ahead of GPT-5.1 Codex and Gemini 3 Pro Preview set to high (both 96 percent).

Behind the news: GPT-5.2 arrived as OpenAI faces heightened competitive pressure. CEO Sam Altman had declared a “code-red” emergency — a level of alarm typically related to smoke and fire in a hospital — on December 1, soon after Google launched Gemini 3. He instructed employees to delay plans to add advertisements to ChatGPT and instead focus on improving the models. OpenAI executives deny that GPT-5.2 was rushed.

Why it matters: GPT-5.2’s gains in computational efficiency are stark. One year ago, achieving 88 percent on ARC-AGI-1 cost roughly $4,500 per task. GPT-5.2 Pro achieves 90.5 percent at around $12 per task, roughly 390 times less. Extended reasoning is becoming dramatically more accessible.

We’re thinking: Technical approaches that aren’t economically feasible today, say running hundreds of reasoning attempts per problem or deploying thousands of reasoning-heavy agents, are on track to become surprisingly affordable within a few years.

Adapting LLMs to Any Sort of Data

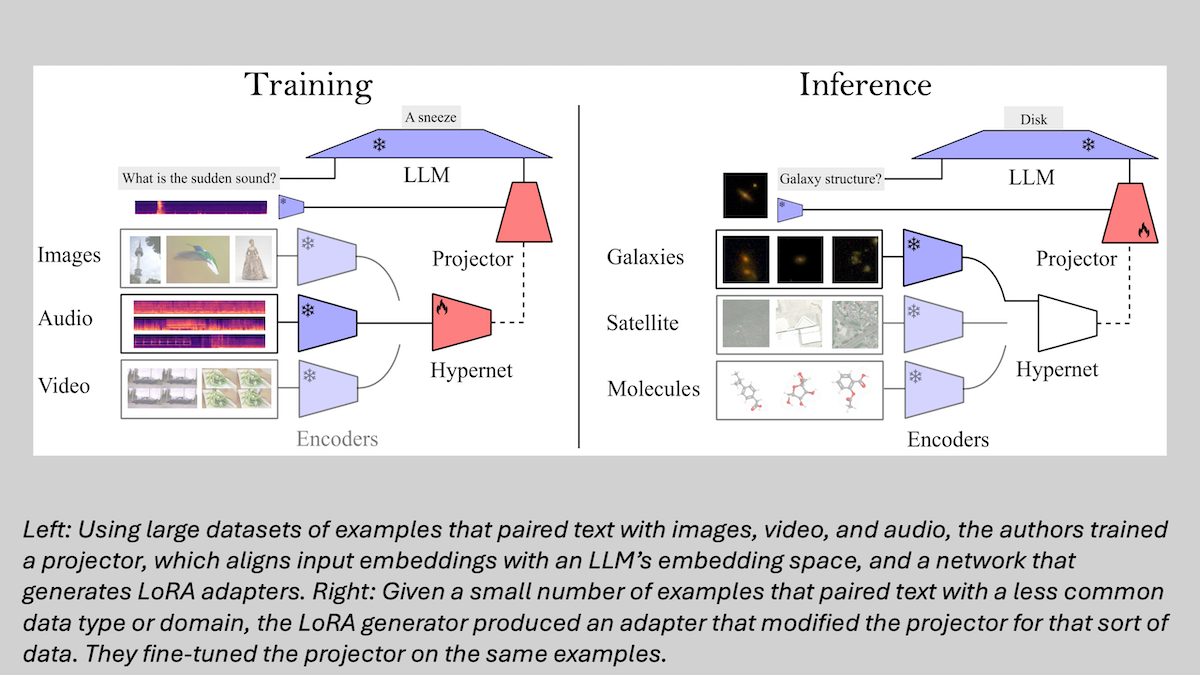

Enabling a pretrained large language model to process a data type other than text (say, images), possibly in a specialized domain (say, radiology), typically requires thousands to millions of examples that pair the other data (perhaps x-rays) with text. Researchers devised an approach that requires a small number of examples.

What’s new: Sample-Efficient Modality Integration (SEMI) enables an LLM to process any input data type in any specialized domain based on as few as 32 examples. Given a suitable, pre-existing encoder, a single projector plus a dynamic complement of LoRA adapters translates input embeddings into the LLM’s embedding space. Osman Batur İnce developed the method with colleagues at University of Edinburgh, Instituto de Telecomunicações, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, and Unbabel, a machine translation company.

Key insight: Typically, adapting a large language model (LLM) to accept multimodal inputs requires training a separate projector for each data type and/or domain. But the ability to adapt to unfamiliar input data types/domains can be considered a general, learnable skill. A projector can learn this skill by training on data types/domains for which examples are plentiful. Then LoRA adapters can adjust it for new data types/domains for which few examples are available. Better yet, a separate network can generate LoRA adapters that adjust the projector to new data types/domains as needed.

How it works: The authors aimed to connect pre-existing, pretrained domain-specific encoders (CLIP for images, CLAP for audio, VideoCLIP-XL for video, and others) to a pretrained large language model (Llama 3.1 8B). To that end, they trained a projector (a vanilla neural network) plus a LoRA generator (a network made up of a single attention layer).

- The authors trained the projector using datasets (around 50,000 to 600,000 examples) that paired text with images, audio, and video. They connected the projector to the LLM, kept the LLM frozen, and minimized the difference between LLM’s outputs and ground-truth text.

- They froze the projector and trained the LoRA generator to produce LoRA adapters based on a description of the task at hand and 128 examples for each data type/domain involved drawn from other datasets of text paired with images, audio, and video. To simulate a wider variety of data types/domains, given a subset of 128 examples, they applied a mathematical transformation to the encoder’s output embeddings while preserving the geometric relationships between the vectors, such as their relative distances and angles.

- At inference, the authors used other pretrained encoders to embed data types/domains the system hadn’t been trained on (for example, MolCA for graphs of molecules). Given a few examples that paired a particular data type/domain with text descriptions, the LoRA generator produced an appropriate adapter.

- To further improve performance, having applied the adapter, they fine-tuned the projector with each adapter using the same subset of examples, keeping other weights frozen.

Results: The authors compared SEMI to training a projector from scratch; fine-tuning their projector; and fine-tuning their projector with a bespoke LoRA adapter using astronomical images from their own dataset, satellite images, IMU sensor data, and graphs of molecular structures plus appropriate pre-existing encoders. They measured performance using metrics that include CIDEr (higher is better), which gauges how well a generated caption matches various human-written ones.

- SEMI beat all baselines in all tests across all numbers of examples (from 32 to the complete datasets of 2,500 to 26,000 examples).

- For instance, on astronomical images with 32 examples, SEMI achieved over 215 CIDEr, while the next-best method achieved 105.

- The sole exception: In tests on graphs of molecular structures, with a few thousand examples, the fine-tuned projector outperformed SEMI.

Why it matters: Large language models are of limited use in many technical fields because little text-paired data is available and building large text-paired datasets is expensive. This work could accelerate adoption of AI in such fields by taking advantage of knowledge in data-rich domains to bootstrap AI training in data-poor ones.

We’re thinking: For AI models to generalize to novel data types, they usually need to be trained on diverse, high-quality data. To that end, it’s helpful to squeeze more learning out of less data.